News & Commentary

Oct 02, 2020

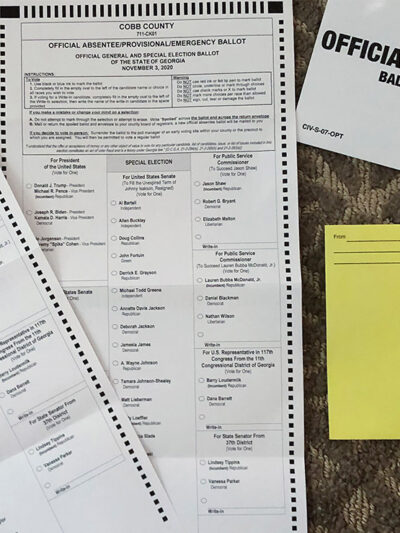

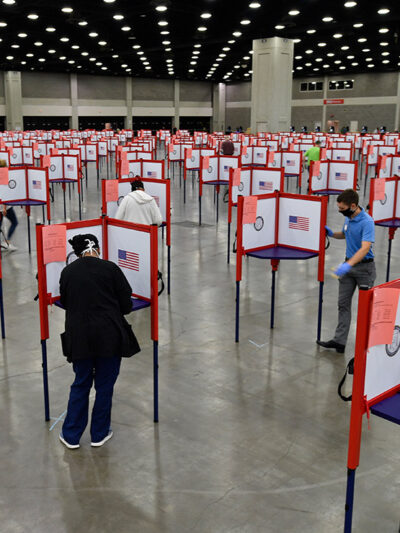

Voting by Mail is Easier and Safer than You Think. Here’s how.

Millions of people are planning to vote by mail in this election, and for most, it will be the first time. COVID-19 has made voting by mail more popular than ever because it’s the safest way for many to cast a ballot. But some voters still have questions about the safety and security of this method, and whether their mail-in ballot will be counted. Contradictory messages from President Trump add to the confusion — even though the president, and many of his cabinet members, vote by mail themselves.

Sep 30, 2020

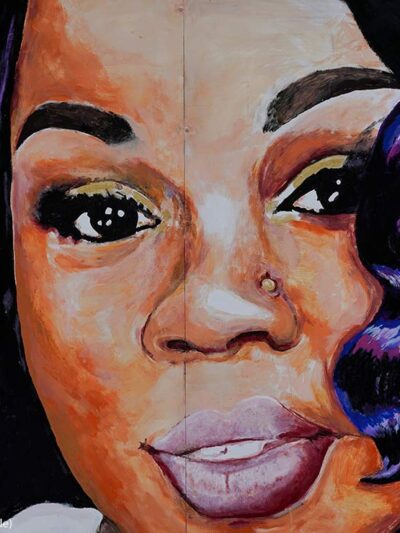

We Are Not Okay

Amber Hikes, they/she, Deputy Executive Director for Strategy & Culture, ACLU

We, your Blac

Sep 29, 2020

Immigration Detention and Coerced Sterilization: History Tragically Repeats Itself

Maya Manian, she/her/hers, Visiting Professor, American University Washington College of Law

The recent ne

Sep 29, 2020

How the ACLU is Flexing its Political Muscle in the 2020 Elections

Ronald Newman, Former National Political Director, ACLU

This

Sep 23, 2020

Remembering an Icon

Ginsburg’s work created ripple effects across the world, inspiring activists and action in the fight for gender relations far beyond the U.S. She was a world-wide icon for dignity, justice, and equality.

By Janna Farley

Sep 21, 2020

Get to Know Your County Clerk

This elected official holds the power to inform and educate voters in their respective counties on upcoming elections, their rights as voters, and more. Get to know them!

Sep 15, 2020

COVID Behind Bars: As Numbers Rise, Wyoming Needs to Take Action

Mass incarceration was a major public health crisis before the outbreak of COVID-19. But this pandemic has pushed it past the breaking point.

By Antonio Serrano, Antonio Serrano

Sep 14, 2020

Get Out the Vote, Wyoming!

Voting is paramount to a healthy democracy, but it’s only effective if we take the time to make our voices heard at the ballot box or absentee.

By Antonio Serrano, Antonio Serrano

Sep 11, 2020

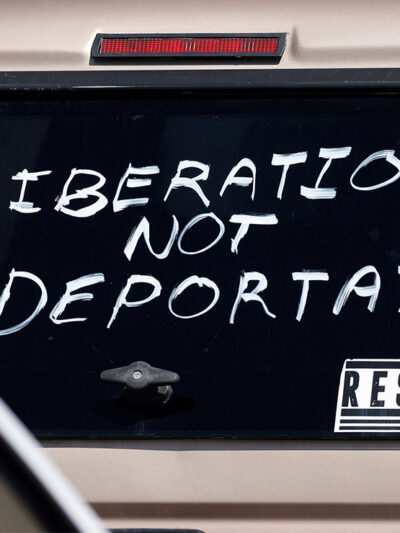

The Myth of the “Bad” Immigrant

Immigrant communities are often asked to “get right with the law,” but is the law right in the first place? That’s what Alina Das asks in her new book, No Justice in the Shadows. She delves into her experience as the daughter of immigrants, an immigration attorney, and a clinical law professor to explore the intersection of immigration and the criminal justice system.

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.